Padded Bosoms and Cork Rumps: Understanding Satire on British Fashion in the 1770s and 1780s

March, 2022

Introduction

Figure 1. 1784, or The Fashion of the Day (1784).

The satirical image above, entitled 1784, or, The Fashion of the Day at first glance appears to be a print that exemplifies the sartorial range of Georgian England. Upon further examination, the satire begins to stand out. The woman in the front takes up central focus in her wide, frilly dress and large hat while the other women sport cork rumps and large plumage. Men gaze at the women as they all engage in a high class social event. Small dogs run around the crowd’s feet playing with each other. While Britons of the late eighteenth century would have likely worn clothing that was similar, this caricature is a slight overstatement of period dress. As the title suggests, this was one satirist’s perception of the fashionable trends in the 1780s. This piece makes fun of the large silhouettes, fashion forward plumage, and other components of dress that were on trend for British elites during the late eighteenth century. Prints like this one, mocking the excesses of fashionable dress, were widespread in the late eighteenth century and reached a peak in the 1770s and 1780s. Many of them went much further than the gentle mockery of this image. This print and others like it, funny though they may be, actually speak to underlying interests and anxieties of those people they were printed for.

The targets of these satires were members of the social and political elite, a group referred to at the time as the beau monde, ton or bon ton. ¹ Members of this group, almost all of them from the titled aristocracy, combined social, economic, and political power. The eighteenth-century beau monde developed along with the rise of the London "Season," when parliament met each year between November and June. Thanks to a now regular schedule of legislative sessions, London further expanded as the social and cultural center of Great Britain. Membership in the ton was demonstrated through participation in politics, attendance at court, and, equally importantly, through public displays of sociability and conspicuous consumption. Historian Hannah Greig explains that this behavior was viewed as an essential element “of noble obligation and modern government.”² All told, this elite consisted of “a few hundred individuals in any one year and most probably no more than three or four thousand over the century as a whole,” yet their influence on British social and political life was vastly disproportionate to their numbers. ³

The beau monde wielded outsized power; however, they were also the target of a growing body of social and political satire. Satirical prints were introduced early in eighteenth-century England as a result of an expanding publishing industry and the lapsing of censorship laws. These were published alongside up and coming newspapers and periodicals that grew with the audience at the time. As literacy increased, so too did the group of people who were accessing printed materials. Satire also had many different themes ranging from politics and specific political figures, to animals in the home, and of course, fashionable dress. This paper will explore the massive growth of satirical images targeting fashionable members of the ton and will seek to explain why those images took the specific form they did.

In order to better understand the booming satire industry associated with dress, I will draw primarily on two existing approaches to the history of eighteenth-century fashion in England. Costume historians focus on the physical makeup of historical apparel and the components that differentiate popular trends. This category of scholarship is deeply researched and typically provides a great deal of information about how dresses were made and worn, but it lacks a perspective on the wider context surrounding fashion more broadly. Social historians, on the other hand, concentrate their research on the sociopolitical statements that were made through sartorial displays.

We can see a typical example of the work of costume historians in an article by Kendra Van Cleave and Brooke Welborn on the robe a la polonaise. The authors explain how this particular fashion has been misrepresented by past historians, and they go into great detail about the actual makeup of a true polonaise. For instance, they identify the tying up of the skirt in three distinct “swags” as a main identification point of polonaise and the most notable distinction from the robe a l’anglaise.⁴ As for the top of the polonaise, they identify the looser corset that made this gown more comfortable than the other robes.⁵ According to van Cleave and Welborn, the polonaise represented an important turning point in clothing design during the late eighteenth century.⁶ While they provide a great deal of scholarly information, they do not tie this transformation to a broader social or political context, instead focusing specifically on the fabrication of the garment itself.

On the other hand, social historians of fashionable England take a more nuanced view of the ton by focusing on the ways fashion worked to define and reinforce social status. A good example of this comes from Hannah Greig in her book The Beau Monde: Fashionable Society in Georgian London. She provides a detailed account of the physical possessions and other fashionable life choices that contributed to one’s status within the beau monde. Greig makes the case that the beau monde was a social structure with a distinct collective identity, one that was carefully policed by its members. Fashionable members of the ton safeguarded the exclusivity of the group by requiring the elite to purchase and portray the right things and engage with the right people, using the proper etiquette. Greig uses consumable goods (e.g., candles), leisure activities (e.g., pleasure gardens and the theatre), and of course dress to demonstrate the importance of consumerism and sociability to the ton. Consumption of fashion was one of the core ways the members of the ton expressed their identity and determined who was included and who was not. The beau monde was situated within the wider political world, and their top rank within the class structure ensured that they were set apart from working-class and middle-class Britons. Ultimately, dress and outward appearance touched many facets of daily life for members of the ton. Though Greig employs a wide lens in her view of the fashionable elite, her focus on the interconnectivity of dress and broader political issues is particularly notable in the context of this paper. Greig’s detailed scholarship offers a helpful framework for looking at the beau monde as a social group and identifying what constituted one’s membership in, banishment from, or leadership of this high society.

Greig also analyzes beau monde politics in her article “Factions and Fashion: The Politics of Court Dress in Eighteenth Century England.” In this article, she argues that court dress was a significant topic of discussion throughout the 1700s, noting the wide variety of newspapers, manuscripts, and letters that discussed not only what people wore to court but also the deeper political meaning behind such sartorial displays. For instance, choosing to wear fabric or other goods manufactured in Britain could be an important way to signal support for national trade. Court dress was a major expense for women, and a display of new clothing at court made a strong statement of support for the monarch. Choosing to wear old clothes, on the other hand, might signal opposition to the court or its political allies. Those reporting on dress thus viewed court fashion as a statement of political faction. Greig’s scholarship provides a valuable framework for understanding how something as apparently apolitical and trivial as clothing could in fact have much broader implications.⁷

Another helpful example of the social history of fashion comes from Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell. She argues that Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire was a particularly good example of the elite, fashionable group of women within the ton who exemplified Whig values through dress. Georgiana was thus opposed to the ruling Tories and their allegiance to a “prudish and modest” crown. Georgiana used her French connections, such as Marie Antoinette (a fashion icon in her own respect) to further establish her position amongst fashionable society. In reference to Georgiana, Chrisman-Campbell states that this relationship between the two women “was a key link between French and English fashion at a time in history when each country depended upon the other for inspiration and innovation.” ⁸ One example that she notes is Georgiana’s displays of feathers in her headdresses, a style that she brought over from France.⁹ Queen Charlotte disapproved of such foreign displays and went so far as to ban feathers from headdresses at court.¹⁰ While the Tories and the royal family sought to establish their "Britishness" by wearing British-made fabrics in styles that had changed little over the decades, Georgiana signaled her own political allegiances by choosing to don the latest French fashions.

Historians like Greig and Chrisman-Campbell focus specifically on the sociopolitical meaning of fashion by looking at actual behavior. The discipline of art history provides another useful perspective on the period. The burgeoning industry of satirical prints in the eighteenth century has attracted attention from scholars like Diana Donald. In her book The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III, she undertakes the daunting task of explaining the social context behind many different facets of Georgian caricature. Donald finds that there was a growing audience for satire as a result of the changing socio-economic conditions in England. A new middle class formed the primary audience for a growing industry publishing prints and newspapers, while the publishing business itself formed an important new middle-class occupation. Donald delves into a variety of topics including the fashionable world and middle-class perceptions of it. She argues that although Protestant moral values were common across the different socio-economic classes, politics and class divisions caused conflict. The excesses across different aspects of life for the bon ton were a point of particular contempt.

This essay brings together the methods and perspectives of both social historians like Greig and art historians like Donald to provide an in-depth analysis of satirical prints aimed at fashionable society in the 1770s and 1780s. I argue that the prints focused on particular elements of female dress from the period: its distortion of the female figure and its excess. But beyond just mocking the fashion itself, such satires reflected deeper social and political currents of the time, including increasing nationalism and anti-French sentiment, the growth of a new middle class, and women's changing roles and visibility in British society. To get at these issues, I will first survey changes in fashionable dress in this period to then demonstrate elements that satires focused on and the degree to which they exaggerated those trends. I will then analyze exactly how satirists mocked these fashions. Satirists portrayed fashionable dress as distorting the female body, often in an explicitly sexualized manner, and as requiring excessive and impractical ornamentation. Finally, the paper will set out the political and social changes of the period that explain why these elements of fashionable dress attracted so much attention and mockery.

This paper will focus on satirical prints, and it is important to consider what we can and cannot learn from them as sources. As Diana Donald has shown, such prints were incredibly popular in the eighteenth century, reaching a wide audience. Over the course of the century, print became increasing accessible, not only to the elite but to the “middle sort” of people that had been excluded from literary media for centuries prior.¹¹ Donald states, “Caricature prints were produced in such numbers, and disseminated so widely, in the later Georgian period that a high level of demand for them must be assumed; evidence of their huge popularity can indeed be found scattered in private correspondence and other records of the period.”¹² This is to say, caricature had a wide array of publishers, a large number of products, and an ever increasing audience. Yet there are limitations to these sources. We cannot, for instance, know with any certainty what the impact of such prints was on public opinion. We have little information about how audiences responded to particular images; similarly, since many prints were produced anonymously, we also know little about the artists who created those images. Nonetheless, it is clear that the demand for satirical prints was large and growing over the course of the eighteenth century. Because these prints were mass produced for sale, we can assume that the creators sought to meet audience demand and to produce images they thought would appeal to viewers. The large number of prints from the 1770s and 1780s that addressed similar topics in similar ways strongly suggests that they represented the concerns and interests of a broad audience.

Changes in Fashionable Dress in the Late Eighteenth Century

Figure 2. Hooped Petticoat and Stays (c. 1760-1780).

Figure 3. Mantua and Stomacher (c. 1708).

Before we examine the satire of the period, it is helpful to understand changes in the way fashionable women actually dressed during the period. Doing so requires examining a variety of primary sources. Surviving examples of dress from the eighteenth century provide direct evidence, but they are relatively rare and likely show particularly elaborate gowns or ones created for special occasions.¹³ Textual evidence, such as descriptions of apparel in newspapers or letters, can provide useful detail and confirm that dress was in fact an important part of society, but it lacks visual references for the modern reader. Illustrations from the period, like those in magazines depicting fashionable dress, provide visual evidence but raise the question of just how literally this kind of artwork can be taken. Bringing together all these kinds of sources can provide a composite view of fashionable English dress.

Eighteenth-century English fashion demonstrates how trends can change drastically over the course of a century. This was in part because of the increase of disposable income, fluctuating moral sensibilities, and a shift to comfort and practicality among female participants. The change from large hooped court dresses that transformed the female form, to the statuesque neoclassical gowns that exemplified the natural woman, took the whole century. Because this paper is focused on the 1770s and 1780s, this section will focus on the key transitions within fashionable dress of the latter half of the century.

Mantua dresses, named for the Italian city of Mantua, are the main example of acceptable court dress of Georgian England. Mantua gowns can be defined as a Hanoverian fashion characterized by a long hooped skirt (worn with a petticoat) to emphasize a wide hipped silhouette.¹⁴ They were prominent from the 1690s to the 1760s. Mantua gowns were notable for their large skirt silhouette (figure 2), fine fabrics with floral embroidery, and tight accentuating corsets to confine the waist.¹⁵The earliest surviving example of a mantua dress is from 1708 (figure 3). This early gown, while not the most drastic, is suggestive of the trends to come. The tall lace headdress, emphasis of the rump through pickups and a long train, fine silk fabric, and the bright contrasting stomacher that calls attention to the chest, all speak to the incoming trends.¹⁶The mantua style reached its peak around the 1750-60s, with massive hoops and panniers that could extend several feet. Figures 4 and 5 provide examples of how this style exaggerated the hips specifically. Although this style fell out of fashion midcentury amongst wealthy, fashionable individuals, it was still required in a court setting.

We know these striking mantuas are representative of the prevailing court fashion because they are supported by other primary source evidence. Figure 5, an etching of the Court at St. James Palace, backs up this assertion. This example is from around 1766 when the style was popular in a court setting, as the title would suggest. The silhouette of the mantua is not lost on the artist making the etching. The women are wearing the box-like hoops or panniers that emphasize the hips. Furthermore, the intricacy of these dresses is also an important, albeit secondary, component of this etching, as seen with the woman in the foreground. Lace sleeves and floral embroidery detail the dress in a similar fashion as the examples outlined above.

Starting in the 1730s, mantua dresses gave way among fashionable women to a new group of styles commonly referred to as robes. Scholar and fashion historian Susan North notes, “By the 1770s the silhouette of the petticoat had evolved into a round shape for all but the most formal styles; a wide hoop was still required for court and evening dress.”¹⁷ Mantua gowns inspired these new sack ¹⁸dresses, including the robe a la française, robe a l’anglaise, and robe a la polonaise, but the rounder shape and narrow hips of the robes exaggerated the rump in a distinctly different way than mantuas.¹⁹ These dresses were characterized by slimmer proportions and were therefore easier to move in. While the specifics of these dresses are not necessarily critical to understanding the satire around dress, they are important to discuss in the context of changing dress during the century and terminology surround specific styles. The robe a la française, popular from the 1730s to the 1780s, is similar to a mantua style, with the same boxy silhouette created by side panniers (figure 7). The robe a l’anglaise (figure 8), popular during the same time frame as the française, is significantly less formal, as seen through the lifted hem hovering over the ground. In addition, the anglaise signifies a shift in the shape of the bottom of the dress with a circular hoop that keeps volume of the rump without such a boxy, cumbersome silhouette. The polonaise was first popular in France c.1774, and by 1777 it was considered a favorable fashion in England. This style (figure 9) is distinguished by three swooping bustles that aid in the accentuation of the rump, as opposed to the mantua silhouettes that emphasize extremely wide hips. While the emphasis on a round rump in dress did not fully diminish with the shift to polonaise, it is notable for its smaller proportions and “greater ease of movement.”²⁰ It is these “slimmer proportions” that are indicative of the trends to come as the century came to a close.²¹

The dominance of the robes ended abruptly with the neoclassical revival beginning in the 1790s. Figure 10 represents a robe a la grecque that is a trend patterned after ancient Greek dress. Is it typified by the high, empire waist, white muslin or cotton fabric, and simple elegance. It was practical, compared to those robes that preceded it, in the sense that it did not require tightly laced corsets or hoops that made even sitting down or walking through a doorway difficult. The art historian Amelia Rauser notes that “it first arose as artistic dress, used by innovators in painting, theater, and dance across several European cultural centers in their search for a more authentic and expressive art.”²² People were looking to classical styles for inspiration around a lot of different areas of popular culture, and Greco-Roman styles offered a more natural form of expression.²³

Other important elements of fashion were the accoutrements that accompanied dress. More specifically, headdresses, wigs, and feathers were noted in correspondence frequently. It should be noted that these coiffures were not necessarily tied to a specific style but stayed a prominent fashion throughout the late eighteenth century even as they took on different iterations and popular shapes.²⁴ The act of wearing a wig was not purely aesthetic. Rauser explains that “to put on a powdered wig was not to deceive others about one’s natural hair but rather to courteously engage with social norms and to broadcast one’s role and stature in society.”²⁵ Wigs, and how they were styled with fruit, feathers, jewels, and other accessories, were an important component of fashion. Unfortunately, there are no surviving wigs or other headdress components to evaluate in the material record as they simply do not stand the test of time in the same way that clothes can. However, reporting on what women were wearing to court events was a popular subject and a helpful tool for women to stay apprised about what was fashionable. While newspapers and other periodicals consistently described prominent women’s dresses, they frequently described their headdresses as well. Summing up the popular fashions at a royal birthday event, the General Advertiser newspaper in February 1786 noted that the women “were universally ornamented with feathers; almost every female in the room displayed the nodding plume, particularly that called the Vetour, so remarkable for lightness and elegance.”²⁶ The Morning Chronicle, reporting on the Queen’s birthday in 1800, described the dress of twenty-five women in attendance; thirteen of them were listed as wearing feathers, and “the principal plumes worn were Paradise Ostrich, and the new Plume called Seringapatam, which is very light and elegant.”²⁷

It was not just court reporting that spoke to the importance of headdresses and specifically feathers to complete a fashionable outfit. Fashions popular in Paris were also frequently reported, reinforcing this idea that an outfit was not complete without these accessories. In 1789, for instance, the World newspaper included in its description of "Parisian Modes" a new fashion for the neoclassical "robe a la Turque," describing not only the dress itself but the accompanying hat: “The hat is made of white sattin [sic] … it is trimmed at the top, and round the bottom of the crown with a wreath of yellow artificial flowers, and out of the front which turns up, issues five large white feathers, spotted with yellow.”²⁸ Eleven years later, The Courier similarly presented the headdresses as equally important as the gown: “Some milliners recommend feathers in imitation of butterfly’s wings, others [avoid] feathers so as to appear in perfect symmetry with the white straw hats. Ostrich feathers are quite out of fashion.”²⁹ Despite these differences in stylistic preference, plumage was important enough to be reported on and discussed by those engaging in fashionable culture. While there may not be a material record, these detailed descriptions paint a picture for the modern historian to understand their prevalence and even to visualize what was being worn without a surviving artifact.

Like dress, hair also spoke to one’s social status in the eyes of the beau monde and the wider, non-elite, community. In their article “Big Hair,” Margaret Powell and Joseph Roach note that headdresses spoke to one's “different social roles, occupations, aspirations, and conditions.”³⁰ Wigs represented a huge investment because their maintenance was painstaking for the hairdresser, and those wearing wigs were seen as investing a massive amount of their time in having their wigs prepared, powdered, and placed.³¹ This display of sartorial significance was, in this sense, similar to the statements one made through dress more broadly and the substantial investments one had to make to create an effective display amongst their peers of the beau monde.

Surviving garments, illustrations, and contemporary reports thus provide information about the actual styles of the time and how they evolved over the course of the eighteenth century. From the early large scale mantua dresses to the Neoclassical revival at the turn of the nineteenth century, dress underwent significant change throughout the century. These dresses in turn help us understand both the inspiration for aspects of Georgian caricatures of fashion, and the ways in which satirists intentionally misrepresented those styles.

Figure 4. Mantua (c. 1740-1745).

Figure 5. Mantua (c. 1740-1745).

Figure 6. Court at Saint James (c. 1766)

Figure 7. Robe A La Francaise (c. 1775-1780).

Figure 8. Robe A La Anglaise (c. 1770s).

Figure 9. Robe A La Polonaise (1780).

Figure 10. Robe A La Grecque (c. 1800).

Caricature and Sexualizing Fashionable Dress

Figure 11. The Cork Rump, The Support of Life (1776).

Figure 12. The Cork Rump, or Chloe's Rump (1776).

Figure 13. Chloe's Cushion, or, The Cork Rump (1777).

Figure 14. The Siege of Cork (1777).

Figure 15. Robe A La Polonaise, modern recreation (1780s).

Figure 18. The Equilibrium (1786).

As we have seen, the silhouette of fashionable dress changed significantly during the late eighteenth century, from wide panniers to a rounder and narrower form. Rather than addressing this general trend, however, British caricaturists aimed their critique at specific elements of female dress. They focused on cork rumps, padded bosoms, and tight stays to present fashion as distorting the natural female form. They also exaggerated the fashionable headdresses of the time to highlight their excess and impracticality. Notably, earlier elements of fashionable dress, such as the mantua style’s wide panniers, did not face the same wave of satirical attack; nor did satirists mock the high cost of fashionable dress, though that would have been an easy target.³² Their focused critique on particular elements of fashionable dress suggests that these elements spoke to the dominant anxieties and interests of the period.

A good example of how silhouette was criticized can be found in The Cork-Rump the Support of Life (figure 11). In this anonymous print from 1776, a woman with a cork rump sits above the water as a result of her artificial garment. The subject appears immune to the chaos around her as she floats on the water after a boat has capsized, saved from drowning thanks to the buoyancy of her cork rump. In this way, the cartoon, rather than emphasizing the price or newness of the fashion, focuses on the ridiculousness of the fashionable cork rump she wears. Similar satires against cork rumps appeared throughout the 1770s. In figures 12 and 13, both titled Chloe’s Cushion, we see women with large enough rumps to support a small dog. The outrageous exaggeration of the rump through artificial means is clearly a popular rendering of this kind of satire as different publishers, not too far apart in time, placed particular emphasis on this trend. Another example satirizing the cork rump can be found in The Siege of Cork (1777, figure 14). The woman is portrayed with an extreme coiffure with large feathers protruding upwards as she flees flying bottles seeking cork for their stoppers. Her bustle flies up in the wind, exposing the artificial rump that the creatures are targeting.

Prior to the 1780s, the silhouette created by artificial rumps and hoops take the brunt of jokes, whereas busts and rumps together become more linked after 1780, perhaps because the development of the robes a la polonaise and anglaise encouraged women to wear linen kerchiefs over the bosom, which created opportunities for padding (see figures 8 and 15). A particularly good example of this can be found in A Modern Venus (figures 16 and 17, 1786), which shows us what a woman’s body would actually have had to look like should a dress be fitted to her form in the artificial silhouettes popular in robe styles. The Equilbrium (figure 18, 1786) is another overtly sexualized piece of satire that shows a blatant exaggeration of female secondary sex characteristics. The woman is displayed delicately, with subtle facial features, gloved hands and refined shoes. In contrast, her bust, rump, and hat are all blown out of natural proportion. Her natural form is distorted by these fashionable features. Her bust is lifted up and out through a painfully tight corset while the cork rump accentuates in an equal and opposite direction. This concentrates the bodily disfiguration in a simplistic yet pointed way. The body appears fake, an eighteenth-century equivalent to the modern Barbie doll, given the unrealistic and physically impossible figure displayed. While this is just one example, this trend permeated satire in the 1780s. A number of cartoons sexualizing the rump and the bust appeared in 1786, including The Royal Toast, Far, Fair, and Forty (figure 19) as well as The Back-Biters, or High Bum-Fiddle Pig Bow Wow (figure 20). The Royal Toast shows a robe style dress, again distorting both the false top and rear. The Back-Biters used the same trope from the 1770s where dogs accentuate the rump; however, this satirical print also exaggerates the bosom.

Figures 16 and 17. A Modern Venus, or a Lady of the Present Fashion (1786).

Figure 19. The Royal Toast, Fat, Fair and Forty (1786).

Figure 20. The Back Biters, or High Bum-Fiddle Pig Bow Wow (1786).

Explaining The Satirical Explosion of the 1770s-1780s

These prints are not subtle in their sexualizing of the female form, but secondary sex characteristics were not the sole focus for satirists. Caricaturists also mocked headdresses for their unnatural structures and for forcing women to sacrifice mobility or practicality for the sake of trends. Publishers accomplished this by portraying coiffures taller than the women wearing them, which supports how impractical they were. In addition to this, some pieces show women struggling to do everyday tasks like walking through doorways. These examples also begin to showcase the extreme hairstyles that were commonplace for both sexes in the late eighteenth century.³³ The 1770s proved an exceptional decade for satire around huge coiffure in English prints.

In the early 1770s, conical shaped headdresses were a popular subject of satirical criticisms. Depictions of these ridiculous coiffures include The French Lady in London, or The Head Dress for the Year of 1771 (figure 21) and Miss Prattie Consulting Doctor Double Fee About her Pantheon Head Dress (figure 22). The sheer size of the headdresses overshadows the figures of the women. Just as other satires mock fashionable dress for creating an image of women’s bodies out of all proportion to their natural figure, these images present fashion as distorting nature in the name of uninhibited extravagance. The French Lady in London explicitly links these ridiculous fashions to the influence of the French, combining satire against fashions with anti-French sentiment.

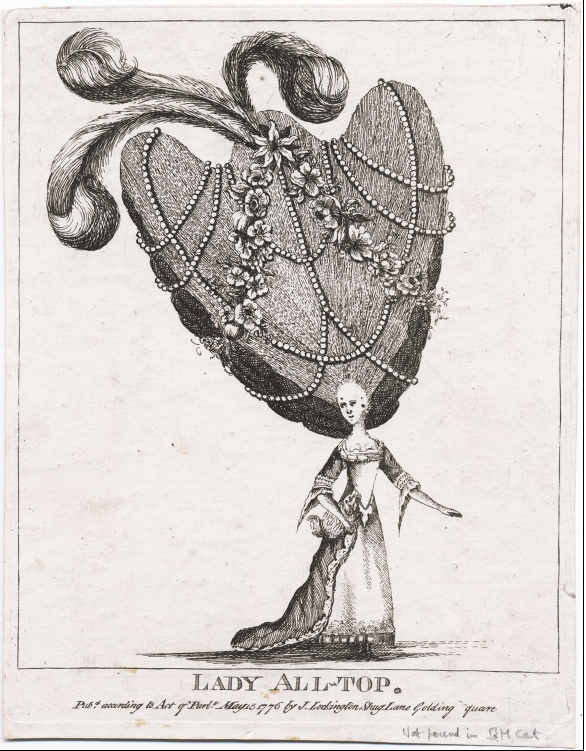

As the decade went on, although the shape of the wigs shifted, the size remained the same. The Extravaganza (figure 23) and Lady All Top (figure 24), both produced in 1776, show a heart shaped headdress adorned with feathers and flowers. More important than the change of shape in wigs is a shift in the satirical presentation of feathers attached to those wigs. Feathers in particular came to embody the fashionable commitment to size and spectacle over proportion and common sense. This is to say, the number of feathers portrayed increased and the size of these feathers grew compared to both the headdresses, women themselves, and their surroundings. Because the trend of large plumage came across the English Channel from France, these examples in turn satirized Francophilia in fashionable British culture.

Figures 25 through 27 demonstrate how satires suggested that feathers specifically impeded women’s ability to engage in otherwise mundane activity. In the print The Vis-a-Vis Bisected, or the Ladies Coop (figure 25), two women are portrayed in the cross section of a carriage, also known as a “coop” in the eighteenth century. They are hunched over even while seated on the floor with little head space or room to move. Each has a significant plumage protruding from their wigs, further impeding their ability to move in the cramped carriage. Phaetona or Modern Female Taste (figure 26), produced in the same year as the Ladies Coop, is yet another example of the emphasis put on feathers in addition to the oversized headdress. Here, the plumage on the woman’s wig is larger than the horses pulling the carriage, and for that matter, the woman wearing them. The Ladies Contrivance or the Capital Concert (figure 27, 1777) applies the same trope of physical impairment as seen in The Ladies Coop. All of these examples show women in a mundane setting of travel while the proportions of the plumage impede their ability to accomplish this task.

The most important part of these prints comes from women sacrificing mobility and comfort for the sake of fashion. The prints depict fashionable plumage as both an impediment and increasingly impractical for women. Notably, in The Ladies Contrivance, the woman is seen in comparison to her male counterpart in the background. Where her carriage has a lifted roof to account for her plumage, this is absent from the male’s carriage. A New Fashion'd Head Dress for Young Misses of Three Score and Ten (1777, figure 28), portrays a similar theme in a different way. Here two men are helping the woman fix and position her headdress. The headdress itself overshadows all the characters as it is taller than all the people when the height of the feathers is taken into account. This speaks to physical impairment because this is not something the woman could do by herself because of the massive proportions at play. A New Fashion’d Head Dress satirizes the woman’s age as well, sarcastically calling the withered crone a “young miss.” This in turn signifies this style is inappropriate for someone of her age.

Feathers were an essential element of many fashionable coiffures, and thus they formed an equally important target for satirists. Additionally, it is important to recall that wearing extravagant plumage, especially ostrich feathers, was seen as an explicitly French fashion, so criticisms of fashionable plumage also acted as criticisms of imported French trends.³⁴ Such critiques were implicit in the prints above, where the plumage in the headdresses creates the ridiculous height and volume. In other cases, attacks focused more directly on the feathers themselves. For instance, birds seem to take the side of anti-French fashion in the print The Feather’d Fair in Fight (figure 29). The birds here are attacking the women’s large plumage, suggesting that it is unnatural as well as extravagant. This mirrors the idea that Britons should also be fighting back against “Frenchified” fashions that in turn take away from a broader British national identity.

Ultimately, fashion in Britain was changing in both how women actually dressed and in the way such trends were perceived by people outside of the beau monde. The lack of mobility, practicality, and comfort, as well as the extravagance of fashionable dress, all came under attack. Satirists suggested that fashion contorted women into unrecognizable shapes and made it impossible for them to engage in basic tasks. The importation of trends from across the English Channel was particularly problematic. The caricatures of women’s fashionable dress came back to the same elements time and again, suggesting that these trends in particular spoke to broader cultural anxieties.

These satirical representations elicited a humorous response in an eighteenth-century context, but to understand why, we need to examine the social, political, and economic climate of Georgian England. As we will see, three critical factors came into play. Anti-French sentiment (and its corollary, anti-Catholicism), the rise of the middle class, and concerns about women’s place in society and politics can all be tied to the satirical representations. Britain was at war with France throughout most of the eighteenth century. National propaganda portrayed France as a popish dictatorship, diametrically opposed to “free,” Protestant Britain. Women were becoming more politically active and more visible in society thanks to opportunities to engage in consumerism and sociability; they were literally as well as metaphorically taking up more space. Finally, the middle class was emerging with new economic power, but without the political power of their elite counterparts. In this context, targeting French trends, fashionable women, and the elite became particularly appealing.

Francophobia led Britons to associate the fashionable world, which was strongly influenced by French trends, with Catholic religious beliefs. The late 1700s was a particularly antagonistic period in Anglo-French relations, which resulted in a dramatic increase in anti-French sentiment, with many British people seeing the French as decadent and elitist. Indeed, British national identity was largely shaped in relation to the French. As Linda Colley argues, “men and women came to define themselves as Britons … because circumstances impressed them with the belief that they were different from those beyond their shores, and in particular different from their prime enemy, the French.”³⁵ In particular, the British celebrated their loyalty, Protestantism, dominance in trade, and relatively free press, all of which they contrasted with the miseries of the enslaved and miserable Catholic French.³⁶ The dueling of the two nations was drawn out, to say the least. Their conflict was unrelenting from 1689 to 1815, and as war dragged on, anti-French sentiment only grew among the British.³⁷ Colley explains the critical factors that made France such a powerful and feared rival: “France had a larger population and a much bigger land mass than Great Britain. It was its greatest commercial and imperial rival. It possessed a more powerful army which regularly showed itself able to conquer large tracts of Europe. And it was a Catholic state.”³⁸ All this to say, there were many reasons why the English wanted to distance themselves from the French, including religious differences, competition, and warfare on a global scale.

Aside from problematic relations with the French, Georgian England also experienced growing conflict between the fashionable beau monde and the up and coming middle class. Historian Roy Porter provides a helpful framework for looking at English class structure by splitting it into seven distinct categories: the great, the rich, the middle sort, the working trades (hard labor), the country people, the poor, and the miserable.³⁹ The eighteenth century saw an expansion of the "middle sort" along with the expansion of trade and growing wealth of the nation as a whole. Members of this middle class also had a strong moral identity, rooted in a deep commitment to Protestantism. One contemporary commentator summed up the middle-class viewpoint as “every man for himself and God for all of us.”⁴⁰ Finally, this group had increasing levels of literacy, which supported a growing demand for news and greater political awareness. This access was supported by the expansion of the press (itself a middle-class occupation) following the lapse of censorship laws in the early eighteenth century. This middle class thus became increasingly aware of the activities of the beau monde, which maintained a monopoly on political power while engaging in behaviors—including indulging in expensive French fashions—that were seen by many in the middle class as decadent or corrupt.

Criticisms of immoral behavior in the fashionable elite were also heavily gendered, partly because of women’s increasing participation in the political sphere. Linda Colley provides necessary context, stating, “Female Britons were in much the same position as the majority of their male countrymen. They might well possess some property to their name. But under the existing representative system, they had no vote. This was one reason why male anxieties about female pretensions became markedly sharper in the second half of the eighteenth century.”⁴¹ For middle-class men in particular, the thought of elite women gaining access to political power while the men themselves remained excluded from that power was galling. In addition, women were active and enthusiastic participants in the expanding opportunities for sociability and consumerism during the late eighteenth century. Their increased presence was in turn deeply worrying to men who were committed to the idea that women should not engage in public life.

While all this was happening, women were physically taking up more space at court, where mantuas (some of which could be more than six feet wide) were a prerequisite for entrance. As Hannah Greig discusses, women's choices in fashion at court also had political implications that were widely recognized.⁴² Where men could make overt political statements, women could also engage with politics through dress. They thus had some access to political influence that middle-class men lacked.⁴³ Satirizing fashions as outsized and impractical simultaneously mocked elite women and dismissed their sartorial decisions as trivial and ridiculous.

Women even engaged in more direct political activity. As Colley notes,

At one and the same time, separate sexual spheres were being increasingly prescribed in theory, yet increasingly broken through in practice. The half-century after the American war would witness a marked expansion in the range of British women’s public and patriotic activities, as well as changes in how those activities were viewed and legitimised.”⁴⁴

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire is a particularly salient example of female political influence in part because she held clout in the context of the court as well as influence over people of lower social rank.⁴⁵ Aside from being a fashion icon, Georgiana was well known for her Whig affiliations and association with the court at Leicester Square, which was overseen by the Prince of Wales and a rival to the court of King George III.⁴⁶ She was so vocal and politically active, she even did electioneering, brazenly canvassing for Charles James Fox. Georgiana took up political space in a context that Chrisman-Campbell describes as “powerful, pleasure-loving Whigs opposed to the ruling Tory party.”⁴⁷ Critics of the duchess and her political allies attacked her for her gambling debts and other ostensibly immoral behavior. For her enemies, Georgiana‘s political activities, devotion to Frenchified fashions, and immoral behavior (like her unpaid gambling debts) were all pieces of the same puzzle. In a patriarchal society, Georgiana and women like her threatened to overturn male dominance over the political realm. If satires against fashionable society were driven by xenophobia, class resentment, and sexism, women like the Duchess represented the perfect target.

Figure 21. The French Lady in London, or The Head Dress For the Year 1771.

Figure 22. Miss Prattle Consulting Doctor Double Fee About Her Pantheon Head Dress 1772 (1772).

Figure 23. The Extravaganza, or The Mountain Head Dress of 1776 (1776)

Figure 24. Lady All-Top (1776).

Figure 25. The Vis-a-Vis Bisected, or the Ladies Coop (1776).

Figure 26. Phaetona or Modern Female Taste (1776).

Figure 27. The Ladies Contrivance or the Capital Concert (1777).

Figure 28. A New Fashion'd Head Dress for Young Misses of Three Score and Ten (1777).

Figure 29. The Feather'd Fair in a Fright (1777).

Conclusion

The socio-political atmosphere of Georgian England created a perfect storm for criticism aimed at women of the beau monde and in turn resulted in a spike of caricature around the matter. Women’s dress was both extravagant and in flux during the eighteenth century, while women were starting to be more outspoken in the realm of politics. Anti-French sentiment coupled with fluctuating class structure and a rise in women engaged in politics created an environment ripe for critique. Ultimately, satires caricatured women of the beau monde and their ridiculous, foreign fashions because they represented everything society was fearful of, in a condensed package of female sartorial display. This did not, however, dissuade women from participating in fashionable society. Instead, women were critical to the neoclassical revival that came at the turn of the century by making their voices and opinions heard.⁴⁸ Despite the satirists' claims, women's fashion in the second half of century was marked by a steady shift toward more comfortable clothes and a silhouette that reflected the natural female form.⁴⁹

While a historian can choose to focus on the political atmosphere that surrounded Georgian fashionable society, the artistic qualities (such as pattern and color) and the underlying trends (changes in silhouette) should not be overlooked. These sartorial displays speak to the large scale social issues that can take up the foreground of historical analysis, as seen when trends of popular style and silhouette changed in line with these broader socio-political anxieties. By marrying political and social history with art history, a larger picture comes into focus. It is by combining sartorial display with socio-political context that we are able to better understand women in the Hanoverian era. Ultimately elite Georgian women embodied the idea that fashion was not just a daily choice people engaged with, but one that spoke to their historic context, socio-economic position, and ability to reveal their socio-political status through the clothing they wore.

These external factors should not, however, take away from the fact that fashion is a personal choice, and as such, it is a form of personal artistic expression that one chooses to make. Amelia Rauser convincingly argues that “Fashion is arguably the most important constituent of an era’s artistic culture as getting dressed is an aesthetic decision that people make every single day and one that situates their bodies in time, space and culture.”⁵⁰ There is a sense of freedom to be found in this sartorial expression that did not go unnoticed in Georgian England, as women experimented with new patterns and changing silhouettes from the 1760s to the 1790s. This freedom was both literal, in these sense that dresses were just physically smaller, less inhibiting in the structure of undergarments, and perhaps more comfortable; it was also metaphorical, in allowing women greater artistic license with color and pattern (e.g. the increased prevalence of striped patterns versus the previously popular floral embroidery). This is not to detract from the political salience that sartorial display had (and has) more broadly, but we should remember that fashion was uniquely personal as well as political. Every time a Georgian woman got dressed, she was making choices about how she wanted to portray herself to those around her. Fashion offered a unique opportunity to make a statement about political allegiance, social status, and personal taste without saying a word.

Endnotes

This terminology was popular from circa 1690 and was out of the common vernacular by approximately 1840. See Hannah Greig, The Beau Monde: Fashionable Society in Georgian London, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 3.

Ibid., 7, 15.

Ibid., 19.

Van Cleave, Kendra, and Brooke Welborn, “Very Much the Taste and Various are the Makes: Reconsidering the Late-Eighteenth-Century Robe a la Polonaise,” The Journal of the Costume Society of America 39, no. 1 (2013): 1.

Ibid., 17.

Ibid., 1-24.

Hannah Greig, “Faction and Fashion: The Politics of Court Dress in Eighteenth-Century England,” Apparence(s) 6, (2015).

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell, “French Connections: Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, and the Anglo-French Fashion Exchange,” Dress 31, no.1 (2013): 3.

Ibid., 4.

Ibid., 5.

Roy Porter, English Society in the 18th Century, (London: Pelican Books, 1982), 53.

Diana Donald, The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996), 15.

Grace Evans, “Marriage a la Mode, An Eighteenth-Century Wedding Dress, Hat, and Shoes Set from the Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum,” Costume 42, (2008).

Susan North, 18th-Century Fashion in Detail, rev. ed., (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 222.

See figure 1: For the purposes of this essay, undergarments are important and distinctive. A hoop petticoat will generally create either a square or circular shape while a side pannier will generally create a box like shape and a cork rump will round the rump without accentuating the hips like these other styles. A hoop is defined by North as “An under-petticoat made of linen reinforced with cane or baleen to create the fashionable silhouettes of eighteenth-century women’s dress” (Susan North, 18th-Century Fashion in Detail, 222).

Susan North provides a helpful definition of stomacher, “A triangular panel to fill in the open front of a mantua, sack or gown.” (Susan North, 18th-Century Fashion in Detail, 222).

Susan North, 18th-Century Fashion in Detail, 29.

North defines a sack dress in her glossary of terms as, “Also sac or sacque. A style of eighteenth-century women’s dress with two double box pleats at the back.” They were also referred to as a negligée during the 1700’s. See Susan North, 18th-Century Fashion in Detail, 222.

The terminology robe will be used going forward to describe dresses that do not fit within the definition of a mantua. These are, generally speaking, less formal dresses outside of the context of a court events that do not have the incredibly wide hip silhouette and will be described in greater detail later on.

Amelia Rauser, The Age of Undress: Art, Fashion and the Classical Ideal in the 1790s, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 9

Ibid, 9.

Ibid, 10.

Ibid, 14.

The terminology coiffure is another French term for a headdress or head and will be used interchangeably.

Rauser, 10.

General Advertiser, February 11, 1786. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspaper Collection.

Morning Chronicle, January 20, 1800. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspaper Collection.

“Parisian Modes,” World, January 16, 1789. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection.

The Courier, August 6, 1800. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection.

Margaret K. Powell and Joseph R. Roach, “Big Hair,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 38, no. 1 (2004): 80.

Ibid., 84.

Donald, 75.

Powell and Roach. 79-99.

See also above pages 13-14.

35 Colley, 17.

Ibid.

Ibid., 24.

Ibid., 25.

Porter, 53.

Ibid., 79.

Colley, 239.

Hannah Greig, “Faction and Fashion.”

Ibid.

Colley, 250.

Chrisman-Campbell, “French Connections,” 3.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Rauser, 14.

Ibid.

Rauser, 8.

Appendix: List of Figures

Figure 1 1784, or, The Fashion of the Day, 1784. The Metropolitan Museum. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/736314

Figure 2 Hooped Petticoat and Stays, 1760-1780. Victoria and Albert Museum, Photo by author.

Figure 3 Mantua and Stomacher, 1708. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/81809

Figure 4 Mantua, c. 1740-1745. Victoria and Albert Museums. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O13811/mantua-leconte/

Figure 5 Mantua, c. 1740-1745. Victoria and Albert Museum. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O78803/mantua-unknown/

Figure 6 The Court at St. James, c. 1766. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:940974

Figure 7 Robe A La Française, 1775-1780. Victoria and Albert Museum. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O74217/sack-unknown/

Figure 8 Robe a la Anglaise, c. 1770’s. Bloomsbury Fashion Central. https://www-bloomsburyfashioncentral-com.du.idm.oclc.org/museumobject?docid=iid-bfl-142571

Figure 9 Robe a la Polonaise, Jane Bailey’s Wedding Ensemble, 1780. Chertsey Museum. https://chertseymuseum.org/brides-revisited

Figure 10 Gown, c. 1800. Victoria and Albert Museum. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O108504/gown-unknown/

Figure 11 The Cork-Rump the Support of Life, 1776. The British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1877-1013-863.

Figure 12 The Cork Rump, or Chloe's Cushion, 1776. The British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_J-5-112

Figure 13 Chloe's Cushion, or, The Cork Rump, 1777. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:292102

Figure 14 The Siege of Cork, 1777. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:292127

Figures 15 and 16 A Modern Venus or a Lady of the present Fashion in the State of Nature, 1786. From a collection of caricatures collected by Horace Walpole. The New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/8c5ee0f5-33a4-dce5-e040-e00a18060296.

Figure 17 The Equilibrium, 1786. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://findit-uat.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:550490

Figure 18 The Royal Toast, Fat, Fair, and Forty, 1786. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:4715651

Figure 19 The Back-Biters, or High Bum-Fiddle Pig Bow Wow, 1786. Lewis Walpole Library. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:553476

Figure 20 The French Lady in London, or The Head Dress For the Year 1771, 1771. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:941230

Figure 21 Miss Prattle Consulting Doctor Double Fee About Her Pantheon Head Dress, 1772. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:5234136

Figure 22 The Extravaganza, or The Mountain Head Dress of 1776, 1776. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:292053

Figure 23 Lady All-Top, 1776. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:292057

Figure 24 The Vis-a-Vis Bisected, or the Ladies Coop, 1776. The British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_J-5-128

Figure 25 Phaetona or Modern Female Taste, 1776. The British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_J-5-89

Figure 26 The Ladies Contrivance or the Capital Concert, 1777. The British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_J-5-127

Figure 27 A New Fashion'd Head Dress for Young Misses of Three Score and Ten, 1777. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:291646

Figure 28 The Feather'd Fair in a Fright, 1777. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:291654

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Archival Material

Digital Collection, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. https://web.library.yale.edu/digital-collections/lewis-walpole-library-digital-images-collection

Printed Primary Sources

The Courier, August 6, 1800. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001360948/BBCN?u=udenver&sid=bookmark-BBCN&xid=15f2528b.

General Advertiser, February 11, 1786. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspaper Collection. link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001694091/BBCN?u=udenver&sid=bookmark-BBCN&xid=4eb53fc6.

The Morning Chronicle, January 20, 1800. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspaper Collection. link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000821207/BBCN?u=udenver&sid=bookmark-BBCN&xid=73e3b9d4.

“Parisian Modes.” World, January 16, 1789. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001511582/BBCN?u=udenver&sid=bookmark-BBCn&xid=dd0c83ef.

Secondary Sources

Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberly. “French Connections: Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, and the Anglo-French Fashion Exchange.” Dress 31, no. 1 (2004): 3-14.

Colley, Linda. Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, rev. ed. 2005.

Donald, Diana. The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996.

Evans, Grace. “Marriage a la Mode, An Eighteenth-Century Wedding Dress, Hat and Shoes Set from the Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum.” Costume 42, (2008): 51-64.

Greig, Hannah. The Beau Monde: Fashionable Society in Georgian London. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Greig, Hannah. “Faction and Fashion: The Politics of Court Dress in Eighteenth Century England.” Apparence(s) 6, (2015): 1-18.

North, Susan. 18th-Century Fashion in Detail. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, Thames & Hudson, 2018.

Porter, Roy. English Society in the 18th Century. London: Penguin Books, rev. ed. 1991.

Powell, Margaret K. and Joseph R. Roach. “Big Hair.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 38, no. 1 (2004): 79-99.